In early 2022, enterprise HR tech startup Darwinbox raised its Series D round, joining the unicorn club. Most observers saw it as a milestone for Indian SaaS, but for 3one4 Capital, one of its earliest backers, it was a defining moment in the fund’s lifetime.

The Bengaluru-based early-stage venture firm from its seven-year-old debut fund — a rare feat in India’s venture capital ecosystem.

The latest exit is an equity sale of the fund’s partial shareholding in Darwinbox. The company closed a $140 Mn round led by Partners Group and KKR. Fund I registered an MOIC of 58.07x and an IRR of 65.08% on its exit.

But getting to this point wasn’t straightforward.

“We launched Fund I in 2016 after almost four years of research,” says Pranav Pai, founding partner and chief investment officer at 3one4 Capital. “It was the most difficult thing I’ve ever done in my life. I thought that would be the end of it. But surprisingly, even today, it’s just as challenging.”

All the more, 2016 wasn’t a rosy time to launch a fund. India’s venture ecosystem was still in its early innings. Tech IPOs were virtually nonexistent and startup exits were limited. India’s consumer internet bubble had just burst. Many global VCs pulled back. Yet that downturn became 3one4’s tailwind.

“Our timing worked out almost prophetically,” he says. “Because we launched during the crash, our entry valuations were highly affordable. For a $16 Mn fund, that was a huge advantage.

3one4 set a clear target: to return the fund — capital plus profits — within its 8+2 year lifecycle. Seven years later, it did.

Fund I is now fully returned with over 1.0 DPI. According to the firm, it is among the first Indian VC funds of its vintage to achieve this within the mandated timeline.

As of date, 3one4 Capital has four funds under management, with its most recent — Fund IV — launched in 2023 . So far, 3one4 has backed 100+ startups and recorded 26 profitable exits across first two funds. “Fund II is now almost a 6- 7x fund,” Pai says. “It was more than double the size of Fund I and it performed much better.”

“When I say ‘profitable,’ I mean getting back more than INR 1 for every INR 1 invested — because anything less than that is not a profitable exit,” Pai explains.

These exits have come through various routes — secondaries, M&As, IPOs and buybacks. “We’ve had many 5-10x exits. The rare ones, of course, are the 50x+ returns. I think we’ll soon have our first 100x,” he adds.

Most of these exits occurred within six years of the initial investment. The firm follows a disciplined approach to liquidity, aligning exits with the fund’s lifecycle commitments. “The harder part is knowing when to exit,” Pai says. “It’s not just logistically hard — it’s emotionally hard. But your job is to return capital on time.”

But before all this came together — the exits and the returns — the biggest hurdle lay at the very beginning: convincing LPs to bet on an untested team building their first fund.

The Early Days: Setting Up The Foundation

The Early Days: Setting Up The Foundation

“I’m an engineer by training,” begins Pranav Pai. “Did my undergrad in Bengaluru, then my master’s in Electrical Engineering at Stanford. My first job out of college was at a SaaS company in the Bay Area — I was employee number three.”

That early startup experience proved foundational. The company, which operated in the HR tech space and sold primarily to Fortune 500 clients, eventually exited in a ~$400 Mn deal. With significant ESOPs, Pai saw firsthand the power of value creation — and value realisation — in the startup world.

“I’m a direct beneficiary of startups working,” he says. “So while I’m an engineer, I was also a systems guy. And my introduction to venture capital came through the lens of an operator.”

As the startup scaled, Pai found himself accompanying the founder on fundraising rounds, meeting over two dozen VCs on Sand Hill Road — some outstanding, others less so. The experience was instructive.

“I realised how much power investors can wield — either accelerating a company’s trajectory with well-timed capital, or sometimes, slowing it down.”

By then, Pai had also begun thinking about his long-term career — and his desire to build in India. Along with a small group of like-minded operators, many of whom were also working abroad, they began exploring the idea of launching a new kind of VC firm in India. That group eventually became 3one4 Capital.

“We didn’t come from finance or venture. None of us were ex-bankers or consultants. We were all operators — people who’d built products, worked inside startups, faced real market feedback,” he recalls. “And that gave us some unique advantages.”

Because the team had firsthand experience navigating startup chaos, they believed they could spot what Pai calls “light signals” of promising companies — subtle indicators of traction or founder depth that traditional VCs might overlook. They also had access: as part of the same under-30 peer set as many rising Indian founders, they were often met with more candor than formality.

Still, the disadvantages were real. “We had no old boys’ network. No LP relationships. We weren’t from VC. And most of the Indian venture scene then was dominated by global brands — US, Chinese, Japanese — who were already on their 9th or 10th fund. We were just getting started.”

More critically, there weren’t many Indian LPs at the time — and Pai was determined to build an Indian VC firm. That posed a problem: how do you raise domestic capital for an unproven fund in a market where exits were rare and local VC credibility still fragile?

The group didn’t rush in. “We studied the space for four years before launching,” Pai says. “It was near impossible. But we were sure India’s economic trajectory was going to change.”

By the time Pai returned to India, GDP had almost doubled. “We saw a $2 Tn GDP addition opportunity unfolding over the next decade — as much value as the country created in its first 70 years. We didn’t want to miss that window.”

Still, the road was far from smooth. The fundraising process itself was grueling. “For our first fund? Maybe 70–80 rejections. Over 10 years? Easily over 1,000. I think a VC manager knocks on as many doors as a founder does.”

Despite all setbacks, Fund I was raised entirely from Indian LPs — mostly family offices and high-net-worth individuals many of whom had never backed a VC firm before. “Many of them met other funds, but they took a chance on us. I’ll always be grateful.”

When 3one4 Capital began raising its first fund in 2016, India’s equity landscape was very different. But even then, public market investors in the country were not new to generating outstanding returns.

“The idea that Indian LPs are not sophisticated is simply not true,” said Pranav Pai, Founding Partner at 3one4 Capital. “They are among the most sophisticated in the world. They understand equity deeply—India has always had a strong culture of investing in equities and public markets.”

At the time, India’s leading companies hovered around a $20–30 Bn market cap, and the total

That created a unique challenge. Venture capital, by nature, is an illiquid and long-horizon asset class. Indian LPs, already comfortable with public market investing, questioned whether the VC risk-reward equation made sense.

“VC is a very weird asset class. You’re hoping to return the principal over 9-10 years. If it works, it’s still a very difficult game,” Pai explained. “In comparison, they could just buy HDFC or go with public market managers like Marcellus—better liquidity, lower fees and proven returns.”

This context made raising domestic capital harder than most first-time managers anticipated. The pitch that typically worked in mature ecosystems wasn’t as effective in India. LPs here demanded clarity on strategy, governance and the fund manager’s edge.

3one4 Capital’s edge came from its operating background. Pai and his co-founders had built and sold software, negotiated large contracts and scaled companies from scratch. They used this experience to design a hands-on, full-stack investment approach.

“We were operators. We’d built companies and sold software. We understood what kinds of firms could scale in India. Our presentation covered the journey—from two guys with a laptop to IPO—step by step,” Pai said.

The team prepared extensively: detailing company-building frameworks, anticipating regulatory hurdles, designing governance systems and crafting founder support systems across multiple funding cycles. This helped them address LP questions with specificity.

The Indian LPs who backed 3one4 weren’t looking for generic exposure to startups. They wanted well-researched, execution-oriented strategies. The firm’s ability to demonstrate this clarity—and its commitment to long-term discipline—built trust.

Over time, this strategy paid off. 3one4 returned capital from Fund I within seven years, delivering strong IRRs and validating its thesis. But Pai is quick to note that this outcome is rare.

“Managers who perform consistently across four or five funds—that’s not normal. That’s the outlier result,” he said.

For 3one4, the combination of operational experience, India-focussed research and a detailed institutional approach helped overcome the early skepticism of domestic LPs. Raising capital in India was never easy—but it was possible with the right pitch, tailored to a very discerning audience, he believes.

Engineering The Exits“When you buy a stock in public markets—say HDFC or Infosys—you’re reacting to many live signals: news, quarterly results, analyst calls, sentiment,” says Pai. “But in private markets, you

cannot always react to those cues. There’s no ticker. No liquidity. No off-ramp on-demand.”

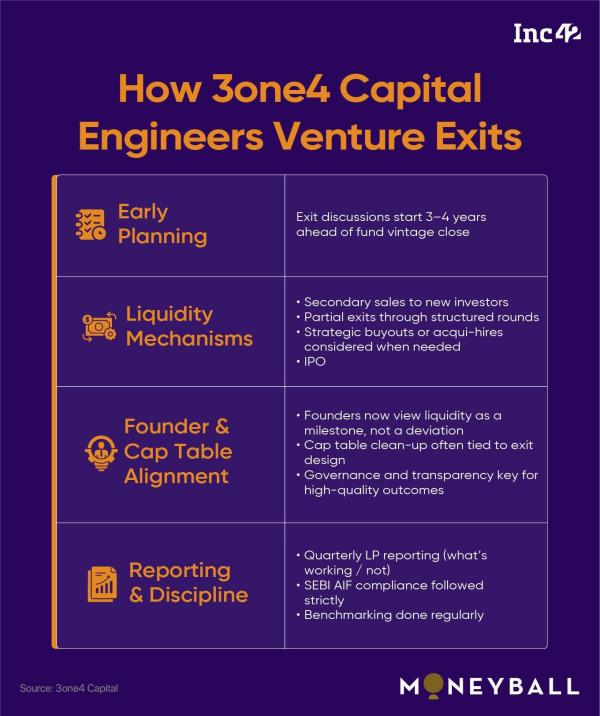

In venture capital, exits aren’t about timing the market. They’re planned years in advance. “We typically start working on exit scenarios 3–4 years before our fund vintage ends. That’s our job—not the founder’s,” says Pai.

And crucially, this planning now has buy-in from founders. There’s a new maturity in Indian startups. Founders understand that exits are part of the cycle. Asking for liquidity isn’t a betrayal—it’s a milestone.

Take Darwinbox. The company wasn’t raising for their runway—they had cash in the bank. In Pai’s words, “That round was structured for early investors like us and for employees to achieve liquidity. That’s a sign of a high-quality company: one that values governance, alignment and value creation across the board.”

Pai also draws a parallel to the historic Infosys moment in 1999 when a wave of employees became millionaires through ESOPs. “Today, many Indian startups are creating the same kind of outcomes—at scale. Founders and boards are proactively designing for it.”

Even in tougher situations, the tone has evolved. “We’ve seen founders come to us and say, ‘This isn’t working—let’s find a home for the company, or at least return capital.’ That honesty is new. And it’s healthy.”

Whether through IPOs, strategic buyouts, secondary sales, or even acqui-hires, the ecosystem is increasingly collaborative. And LPs, according to Pai, are not just chasing exits—they’re demanding discipline.

“Our LPs don’t need to nudge us. We plan exits years ahead. That’s part of our DNA. We’ve

never waited for investor pressure—we act before it is necessary.”

Mistakes aren’t always obvious in venture capital—especially when you’re right more often than not. But as Pranav Pai reflects on 3one4 Capital’s journey, he points to a more nuanced realisation: not all misses look like mistakes at first.

“We’ve always been rigorous,” he says. “Very clear about what the shape of a successful company looks like. And for the most part, it’s worked—our performance shows that. But what no one teaches you is how to deal with upside surprises.”

Here are three key lessons learnt:

Preparing for Downside Is Easy. Upside? Not So MuchVCs often train themselves to manage risk, reduce downside and brace for unexpected shocks—be it a founder fallout, macroeconomic turbulence, or policy events like demonetisation.

“But planning for positive surprises? That’s much harder,” says Pai.

Take KukuFM, for instance—a company that didn’t generate meaningful revenue in its early

years and operated in a category surrounded by free alternatives like music and radio. Today, it

is the largest platform in its space and amongst the fastest-growing in the category globally.

“For five years, it was one of our best-potential companies on growth metrics. But because we had

other winners that broke out earlier in the same fund, we could not double down as aggressively

as we would have.”

In hindsight, he says, that restraint—driven by fund size limits and capital discipline—may have capped their upside.

The Frustration Of Fund Math“The hardest part? Small fund sizes limit your ability to back breakout winners when they’re finally ready,” he says. “If you’ve already allocated capital to other follow-ons, you don’t have enough left to double down on late breakouts. And that’s frustrating.”

It’s a lesson that has stuck with him—how compounding success can sometimes restrict risk appetite instead of enabling it.

The Intuition Gap – What Can’t Be Taught“That’s the paradox. As a disciplined fund, you do all the right things, but when a company turns the corner after a long haul, you may not be able to back them enough. That keeps me up at night.”

Pai calls it one of the most subtle yet profound learnings from the past decade: knowing when to hold out belief in a company that’s taking longer than expected and distinguishing that from misplaced optimism or less aversion.

“There’s no formula for it. And I don’t think it can be taught. But I think about it constantly—the cost of not having an open-enough mindset when something is finally breaking out.”

In the end, venture capital may be about risk, but it’s also about heart. “That’s the real decision tension,” he says. “And it never gets easier.”

[Edited by Nikhil Subramaniam]

The post appeared first on .